Explaining Japanese Yen Strength Despite Weak Economy

Currencies / Japanese Yen Nov 02, 2010 - 10:23 AM GMTBy: Kieran_Osborne

For many, the strength of the Japanese yen is a conundrum. How can the currency of a country with such a weak economy, such a high level of debt, weak leadership, poor demographics, combined with an ever deteriorating economic outlook be so strong? Many market participants did not anticipate that the yen would demonstrate such strength 24 months ago. Now, many commentators focus on Japan’s “safe haven” status as a key reason why the currency has appreciated.

For many, the strength of the Japanese yen is a conundrum. How can the currency of a country with such a weak economy, such a high level of debt, weak leadership, poor demographics, combined with an ever deteriorating economic outlook be so strong? Many market participants did not anticipate that the yen would demonstrate such strength 24 months ago. Now, many commentators focus on Japan’s “safe haven” status as a key reason why the currency has appreciated.

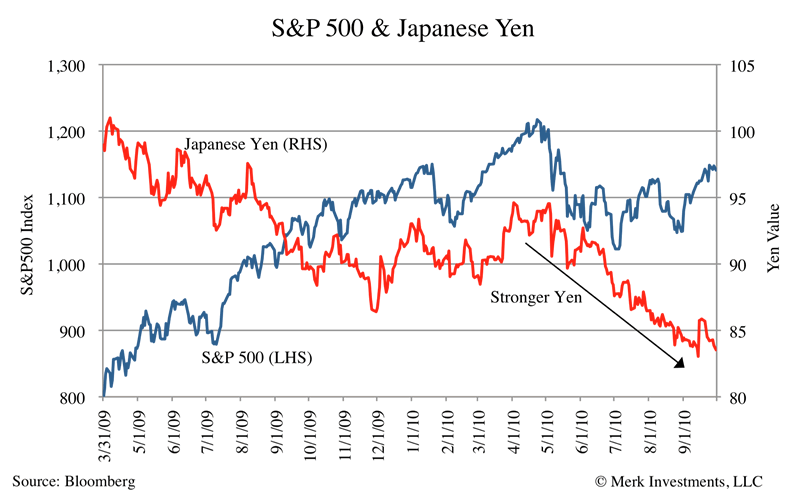

True, at the onset of the financial crisis the Japanese banking system was viewed as being amongst the soundest globally, but as risk came back into the markets in March 2009 through most of that year, the yen continued to appreciate. In a period where we witnessed a substantial reversal in risk aversion (the S&P 500 returned over 50% from the end of February 2009 through December 31, 2009), the Japanese yen’s safe haven status does little to explain its strength.

So what has driven the strength of the yen? While the reasoning behind currency price movements is inherently multi-faceted, we believe some of the more relevant drivers of Japanese yen strength have been: 1) weak leadership; 2) low reliance on foreign investment; and 3) relative attractiveness of Japanese yields.

Weak Leadership:

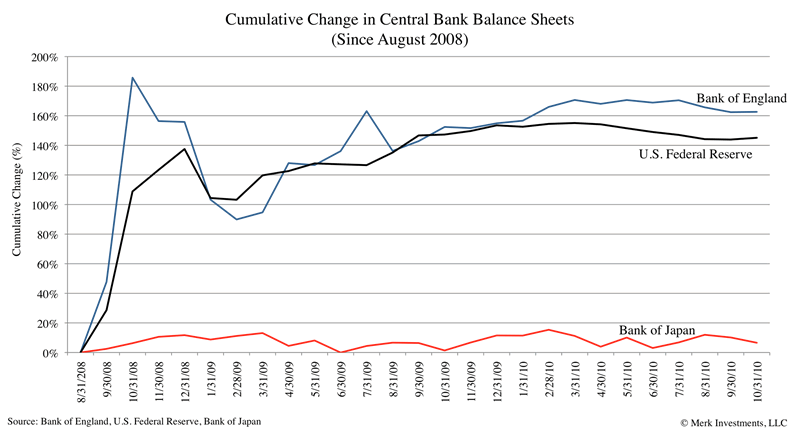

Japan has been through nine finance ministers and five prime ministers since 2006. Let me repeat: nine finance ministers, five prime ministers. Suffice to say, it has been an incredibly unstable political situation. With Japan’s leadership in flux, policy makers lacked any central cohesion. As a result, Japanese policy makers were less focused on printing and spending money. This is particularly evident through Japan’s monetary policies: while other central banks around the world were printing money like there was no tomorrow in response to the global credit crisis, the Bank of Japan was conspicuously absent in its ability to bloat its balance sheet.

The change in a central bank’s balance sheet can be thought of as a proxy for the additional money (currency) that central bank has printed; central banks can purchase securities (whether Treasuries, mortgage backed securities or any other financial asset) with a few simple keystrokes. Creating money out of thin air may be an apt description of this process. This increases the supply of that currency printed. When the supply of any asset increases, this naturally creates downward price pressure on that asset; all else equal, that asset will fall in value. While the Bank of England and the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) printed vast amounts of money, the Bank of Japan did not. Between August 31, 2008 and September 30, 2010, the Japanese yen appreciated 30.25%, whereas the British pound declined 13.70% against the dollar.

Not reliant on foreign investment

There is a common misconception that a country requires strong economic growth to have a strong currency. That is not necessarily true. When a country runs a current account surplus, it doesn’t necessarily need economic growth to have a strong currency. Japan is the perfect example. Japan is not reliant on foreign investors to support its currency; it has had lousy economic growth yet a very strong currency.

Let’s put it another way: In 2009, the U.S. had a current account deficit of $378 billion, meaning that the U.S. required foreign investors to purchase approximately $1.5 billion dollars worth of U.S. dollar denominated assets every single business day just to keep the dollar from falling. In contrast, the Japanese current account surplus for 2009 was ¥13.3 trillion, or using the average exchange rate for the year, $142 billion. Japan required foreign investors to sell over half a billion dollars worth of yen denominated assets every single business day just to keep the Japanese yen from rising. The point here is that a country with a current account deficit, such as the U.S., needs to display economic growth in order to attract investment from abroad to underpin strength in its currency, whereas a country with a current account surplus, such as Japan, does not.

At approximately 200% of GDP, Japan has by far the highest level of government debt of any “developed” nation. However, the vast majority of this debt is financed domestically. In other words, Japan is less reliant on international investors to finance its fiscal deficits. In the U.S., over 50% of privately held Treasury securities are owned by international investors, while in Japan, only around 5% of Japanese government securities are owned by international investors. Japan simply has had a much higher savings rate than the U.S. and therefore its domestic population has been able to support the fiscal largess of the government. While pressure has mounted globally over the unsustainable deficits many governments are running, Japan is an acute case and has been for sometime; Japan’s fiscal situation was considered by many to be chronically unsustainable well before the global financial crisis took hold in 2008. Arguably, Japan’s unique domestic savings situation has protected it somewhat from international political pressures to instigate meaningful austerity measures, though we believe these dynamics are changing, as we will explain below.

Relatively attractive yields

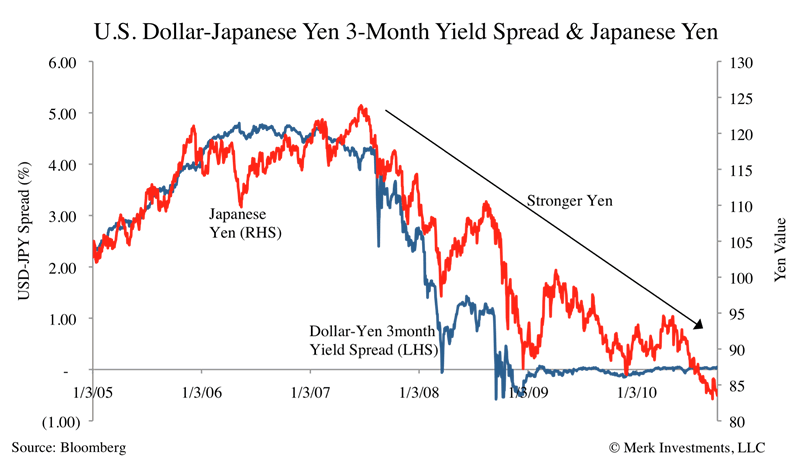

The term “attractive Japanese yield” sounds like an oxymoron given the extremely low rate environment that has prevailed for the past decade, but let us elaborate. Leading up to the financial crisis of 2008, one of the more common currency trading strategies employed was the carry trade. At its most basic level, an investor following a carry trade strategy would short a low yielding currency and buy (go long) a high yielding currency. It just so happened that Japan had very low rates, and countries like Australia had relatively much higher rates. As such, one of the most popular carry trade strategies was to short the Japanese yen and go long the Australian dollar. Once the financial crisis took hold, the carry trade fell apart, as central banks around the world rushed to cut target interest rates and provided unlimited liquidity to the financial industry. However, this did not happen in Japan. Rates were already close to zero and weak leadership meant that the Bank of Japan did not print as much money as its global counterparts. While Japanese yields remained low, yields elsewhere fell, and as such, the low yields in Japan became less unattractive, or, canceling a double negative, relatively more attractive. Indeed, it appears the U.S. dollar became a more attractive substitute for the short side of the carry trade when risk came back into the market in 2009.

The following chart, which depicts the spread between Japanese three-month government securities and equivalent maturity U.S. Treasuries on the left axis, and the value of the yen on the right axis, may help illuminate this dynamic.

The high correlation between the yield spread and the price of the yen is evident from even a cursory glance at the above chart. What’s more, these are nominal yields; given the deflationary environment in Japan, Japanese real yields are quite a bit higher than the U.S.

Where to now?

Has the yen run its course? Possibly, though relative to the U.S. dollar there still may be upside potential given the vast amounts of money the Fed appears ready to spend (“QE2”).

We believe that many of the factors outlined above are losing steam, and from this perspective, the upside potential for the yen appears less compelling. For one, the leadership structure seems to be strengthened. While Naoto Kan has only been Prime Minister since June 2010, he appears to have solidified his position, successfully fending off a challenge to his leadership by defeating Ichiro Ozawa earlier this year. Kan appointed Yoshihiko Noda as Minister of Finance, a position Kan himself filled before becoming Prime Minister.

While a stronger leadership structure might be a net positive for many other countries’ currencies, we believe the opposite may be true for Japan. Policy makers have already attempted to exert their influence to weaken the exchange rate, unilaterally intervening in the currency market selling the yen. While this attempt appears to have been somewhat fruitless (the yen has since appreciated) it does show that the Japanese are actively willing to intervene to weaken the yen. Moreover, the Bank of Japan recently announced an expanded asset purchase program (aka quantitative easing) that could raise the eyebrows of even the most liberal proponents of QE; the expanded program includes purchases of REITs, ETFs, and lower quality corporate bonds. Combine this with the recent semi-annual Outlook Report, where the Bank of Japan outlined its inflation expectations, which were much higher than consensus estimates, implying they believe the expanded program may be successful in generating inflation. We consider it very likely that we will witness an expansion of the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet over the medium term. Contrast this with most other central banks that are either tightening policy, or openly discussing tightening (with the obvious exception of the Fed).

Demographically, Japan faces extreme challenges. In our opinion, the demographics of the country are such that the government will be increasingly reliant on international investors to fund its fiscal deficits. Japan has an ageing, shrinking population. Retirees make up an ever-increasing proportion of the population, while the working population is decreasing. In our view, domestic demand for Japanese government bonds (JGBs) must decrease. As the population ages, retirees move from net savers to net spenders and will be required to sell bonds to supplement their retirement income (either directly, or indirectly via corporate pension plans or Japan Post Bank). At the same time, a shrinking working population means a lower population base to substitute the retiree sellers, and less tax revenues at a time when entitlement expenditures are increasing. Put simply, the Japanese government faces an increased need for funding (increased supply of JGBs) while there will be a decrease in domestic demand. As such, Japan is likely to have to rely on foreign investment to fund its fiscal deficit going forward. We would contend that when this point is reached, it may represent an inflexion point for the currency.

Japanese policy makers appear aware of this threat, recently embarking on an aggressive (if not somewhat humorous) marketing campaign to sell government bonds to the younger domestic market. In what is reminiscent of a cheesy infomercial, the government has hired models and TV personalities to promote government bonds, with such slogans as “Men who hold JGBs are popular with woman!” You couldn’t make this stuff up. Wait a second… If the same relationship holds for U.S. Treasuries, there must be a lot of broken hearts in Washington over the fact that Mr. Bernanke is already spoken for. But I digress…

On a more serious note, the Japanese government has announced plans to rein in government spending, to implement more austere measures over the long-term, presumably realizing that if they don’t do something now, international investors will force it upon them down the road, at which stage it may be too late and/or the situation may have deteriorated to such a point that the government simply will not be able to access funding internationally at interest rates it can stomach.

However, the real problem is the size and scope of the issues Japan faces. It may already be too late. By implication, when Japan becomes reliant on foreign investment to fund its fiscal deficit, it will be in a worse situation than present. To get to such a point, supply of JGBs and domestic demand will have moved in opposite directions (supply up, domestic demand down). Investors are likely to demand an increased risk premium given the size of the fiscal debt, which in itself may start a vicious cycle, given more tax revenue will need to be spent on interest charges, while overall tax receipts are likely to decline as the population continues to shrink, driving up the need for even greater levels of debt.

Make no mistake about it: Japan may face a very scary future going forward, and it may only be time before these risks are adequately factored into the price of the Japanese yen.

Ensure you sign up for our newsletter to stay informed as these dynamics unfold. We manage the Merk Absolute Return Currency Fund, the Merk Asian Currency Fund, and the Merk Hard Currency Fund; transparent no-load currency mutual funds that do not typically employ leverage. The Merk Hard Currency Fund can be considered an international fixed income fund with a firm commitment to the short end of the yield curve. To learn more about the Funds, please visit www.merkfunds.com.

Kieran Osborne

Merk Mutual Funds

Kieran Osborne is Senior Analyst and member of the portfolio management group at Merk Investments; he is an expert on macro trends and currencies and has significant international market experience. Prior to Merk Investments, Mr. Osborne was an equity analyst at Brook Asset Management, where he worked in both the Australian and New Zealand markets. He has also worked in New York for MCM Associates, a U.S. hedge fund.

The Merk Asian Currency Fund invests in a basket of Asian currencies. Asian currencies the Fund may invest in include, but are not limited to, the currencies of China, Hong Kong, Japan, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand.

The Merk Hard Currency Fund invests in a basket of hard currencies. Hard currencies are currencies backed by sound monetary policy; sound monetary policy focuses on price stability.

The Funds may be appropriate for you if you are pursuing a long-term goal with a hard or Asian currency component to your portfolio; are willing to tolerate the risks associated with investments in foreign currencies; or are looking for a way to potentially mitigate downside risk in or profit from a secular bear market. For more information on the Funds and to download a prospectus, please visit www.merkfund.com.

Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks and charges and expenses of the Merk Funds carefully before investing. This and other information is in the prospectus, a copy of which may be obtained by visiting the Funds' website at www.merkfund.com or calling 866-MERK FUND. Please read the prospectus carefully before you invest.

The Funds primarily invest in foreign currencies and as such, changes in currency exchange rates will affect the value of what the Funds own and the price of the Funds' shares. Investing in foreign instruments bears a greater risk than investing in domestic instruments for reasons such as volatility of currency exchange rates and, in some cases, limited geographic focus, political and economic instability, and relatively illiquid markets. The Funds are subject to interest rate risk which is the risk that debt securities in the Funds' portfolio will decline in value because of increases in market interest rates. The Funds may also invest in derivative securities which can be volatile and involve various types and degrees of risk. As a non-diversified fund, the Merk Hard Currency Fund will be subject to more investment risk and potential for volatility than a diversified fund because its portfolio may, at times, focus on a limited number of issuers. For a more complete discussion of these and other Fund risks please refer to the Funds' prospectuses.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.