Is an International Currency Crisis on the Way?

Currencies / US Dollar Oct 29, 2007 - 09:18 AM GMTBy: Gerard_Jackson

In trying to resolve the basic issue of where prices go from here, we have to balance short-term market momentum against the increasing drag of economic reality and we have to weigh the price enhancing effects of inflationary monetary policy and deliberate currency neglect against the price depressive ones of a meaningful frustration of current entrepreneurial assumptions. We then have to grope towards some tentative conclusions on the vexed issue of whether the cycle in Asia (and, indeed, in Continental Europe) has achieved sufficient automotive power for it to ride out any more serious abatement of Atlantic Rim over-demand.

In trying to resolve the basic issue of where prices go from here, we have to balance short-term market momentum against the increasing drag of economic reality and we have to weigh the price enhancing effects of inflationary monetary policy and deliberate currency neglect against the price depressive ones of a meaningful frustration of current entrepreneurial assumptions. We then have to grope towards some tentative conclusions on the vexed issue of whether the cycle in Asia (and, indeed, in Continental Europe) has achieved sufficient automotive power for it to ride out any more serious abatement of Atlantic Rim over-demand.

To take these questions in the order presented, we would never underestimate the Wile E. Coyote ability of leveraged enthusiasm to defy the unrelenting force of gravity for a long, Looney Tunes moment. Thus, the outcome will be signalled best by a combination of technicals and a more subjective assessment of how much potentially explosive cognitive dissonance has built up if increased bullishness actually does come to coincide with a progressively deteriorating data flow.

Regarding the second factor, we can only underline that we feel the price risks being run here by the central banks are extraordinary. Not the least of these is the danger that the US will provoke the fourth great reserve currency crisis in a century ? the previous three being the abandonment of the gold standard during the Great War, the collapse of the gold exchange standard during the Depression, and the break-up of Bretton Woods at the end of the Sixties.

Since this is a tale of the successive adulteration of money and of the serial acceptance of a more bastardized replacement when the burdens of the previous one become too much for political expediency to bear, we can expect profound, if largely indeterminate, consequences to follow ? social and political, as well as purely financial ? if the ailing dollar does, indeed, end up being widely forsaken.

A flight to real values might well be unleashed in such circumstances, boosting prices of selected commodities ? gold, for example ? to unheard of heights. Similarly, the full panoply of protectionism, income support, and the direct administration of prices, which is a likely policy response, could devastate others, either by promoting wasteful over-supply or by inducing a nasty and protracted recession.

Finally, as for the possibility of Asian insulation, our intuition is that the Sinophiles might well be right ? but perhaps not for another fifty years, or so. As regular readers will be aware, our basic premise is that a producer-led credit boom leads, in course, to a perilous over-expansion of certain lines of business to the point that the relevant firms become utterly dependent on further, ever more powerful injections of that same credit.

But if this hypertrophy has taken place anywhere in the past eight years or so, it has done so in Asia. That is, the top of the global (rather than the local) productive structure ? the area likely to be the most distorted by the credit expansion and hence the most vulnerable to its later interruption ? is no longer predominantly to be found in the same sovereign jurisdiction as are the end customers for the goods to which it helps give rise.

Inflation in the West has been much more a matter of funding unearned consumption. As such it has prevented prices from falling, but has shortened, rather than over-lengthened the productive structure. The two main exceptions to this have been in housing and finance, both of which are currently paying the price for their credit-induced gigantism.

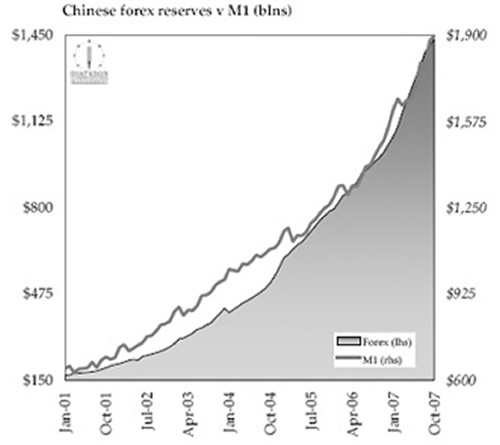

Conversely, it is in the Asian manufacturing centres and in the countries flooded with petrodollars, cuprodollars and farreodollars in which the inflation has been directed into building and equipping industrial plant, erecting office blocks, and laying down infrastructure ? all often on a scale which almost defies the imagination. It cannot be wholly a coincidence that the rapid growth of Chinese M1, for example, of 17 per cent a year compounded since the start of 2001, has been matched dollar for dollar with $1.2 trillion accumulation of foreign exchange reserves under the nation?s crawling peg ? and this in a period when industrial output has trebled, exports have more than quadrupled, and the trade surplus has risen 850 per cent.

If credit expansion and industrial export capacity have not been engaged in an ever brisker paso doble in the Middle Kingdom, then the mechanics of the process have obviously escaped us entirely. It is worth recalling that, in surpassing the prior hegemony of Britain, the US had achieved its own industrial and commercial pre-eminence a good 30-40 years before an economic meltdown in Europe and Latin America (caused by the mass withdrawal of lavish American credit facilities in 1928-9) dealt a severe blow to goods exporters back home in the States.

This helped exacerbate the developing domestic downturn, but not, paradoxically, before giving a last boost to soaring equity prices on Wall St. as the funds were first repatriated (shades of China today?). The foreign ?credit crunch? was therefore instrumental in both triggering the ensuing Crash and, ultimately, in worsening its consequences.

The parallel is obviously not exact, but there are enough echoes of these earlier straitened circumstances to make us wary of a similar denouement today. If a major devaluation of the dollar is what we are to endure in coming months, foreign exporters will not necessarily find that replacement consumers at home will want exactly the same mix of goods and services as did their US customers, no matter how much the formers? purchasing power will have been increased. This means losses will be widespread and adjustments non-trivial, whatever the aggregationists might argue to the contrary.

Conversely, those same US customers will be largely forced out of the market if they cannot supplement falling real incomes with the same easy access to vendor finance from abroad that they have enjoyed to date, which is what an abrogation of present, dollar-centric reserve arrangements clearly implies.

Thus, even if the Fed were able to inflate with sufficient determination to limit the impact on domestic dollar borrowing rates (though this might be a particularly difficult trick to pull off at the long end), this would only come at the cost of intensifying the pressure on the already sickly currency and might, therefore, do little to support already shrinking import volumes. The impetus towards an Asian slowdown would be all but inevitable in such a case.

As for the home-grown ramifications, it is little wonder that Bill Gross recently told a TV interviewer that though he felt we were due another year or two of broadly favourable conditions for fixed income, this would be the last such occasion for a generation and that, even given his expectation.

By Gerard Jackson

BrookesNews.Com

Gerard Jackson is Brookes' economics editor.

Gerard Jackson Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.