Low US interest rates ignited unsustainable asset bubbles - Connecting the dots

Interest-Rates / Analysis & Strategy Jan 26, 2007 - 04:17 PM GMTBy: Dr_Martenson

Can you possibly stand another article about Greenspan? If the answer is “no” I completely understand – I too am ready to let the man take his place in history next to the buggy whip – but he was responsible for something that will be resonating in your life for a very long time.

Since I've already typed two complete sentences and am still on topic, I think it's time for a detour. So let me tell you that I am cursed with a brain that connects dots. Worse, my brain likes to store things up as though random news items were potatoes and a particularly vicious Polish winter were on the way. The fact that I live in the US only confuses things all the more.

But that's not the point. The point is that Alan Greenspan is either depraved or a fool and, of the two, I am not sure which I feel worse about as describing the man who was at the helm of the monetary bobsled during the longest stretch of paper credit expansion the world has ever seen.

Let's play ‘connect the dots':

1. In December 2002, private bankers warned Greenspan that consumers were taking on worrisome amounts of debt and that an unsustainable, interest rate driven housing bubble was fueling this behavior (page 22 of this linked document) .

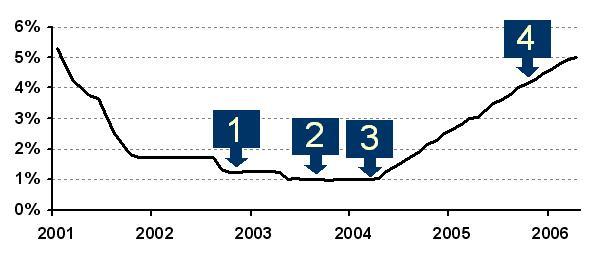

2. In July of 2003 Greenspan lowered interest rates to one-percent (as in 0%, or one-point-oh ), an emergency rate, and held it there for over a year (see chart below).

3. In February of 2004 Greenspan advised Americans that they'd be better off with adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) than they would with fixed rate mortgages.

4. In October of 2005, the new bankruptcy law, largely written by private banking lobbyists and insiders, was passed.

Here's how those data points look when plotted out on a chart of short-term interest rates:

To summarize; (1) Mr. Greenspan was warned that he was igniting an unsustainable asset bubble, (2) he threw more gasoline on the fire, (3) he then advised consumers to switch to ARMs right before what he knew (for certain) would be a protracted period of rising interest rates, and then (4) kept mum while bankers worked feverishly to pass bankruptcy legislation that was indisputably banking-friendly but a consumer nightmare. Kind of sounds odd when you put out there like that doesn't it?

Now here's the interesting part about the story. To consumers, Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs) are good or bad depending on whether interest rates are rising or falling. When interest rates fall the ARM adjusts down with them. The reverse is true when rates are rising.

As the following highly technical table makes clear, you really, really don't want to be holding an ARM during a rate hiking campaign.

Table 1 |

Interest Rates |

|

Mortgage Type |

Rising |

Falling |

ARM |

BAD, BAD, BAD |

Good |

Fixed (Conventional) |

Good |

Bad |

Clearly, when interest rates are about to embark on a sustained rise the best advice to consumers would be to lock in a low rate conventional mortgage.

But when we refer to the four data points in the chart above, we observe that Mr. Greenspan advised consumers to take advantage of ARMs right before the onset of what he knew would be a multi-year rate hiking campaign. Obviously he advised people to do the exact opposite of what they should have done. Why did he do that?

We can look at this two ways. On the one hand we could assume that Mr. Greenspan is a very poor banker and that despite his long career in banking he did not have access to the requisite highly technical information (see Table 1, above) and was simply unaware that it was very bad advice to steer people towards ARMs mere months before the onset of a protracted rate hiking campaign. On the other hand we could assume Greenspan knew exactly what he was doing and conclude that his motivations lay with shielding the banking industry from rising interest rates by cajoling consumers into ARMs at the very worst possible moment in the past 50 years.

Naturally, I'd like to assume the best but given the two options, I'm not sure which horse to root for. If I hope he was just a fool, what hopes should I pin on our chances for an agreeable resolution to the credit bubble he created? And If I'm to assume that all his actions were a depraved attempt to shield large banking institutions from a bit of risk then I need to accept the possibility that all of his policies were geared towards promoting institutions over people.

So which is it?

History will tell, but the early returns suggest you would be better off getting your financial advice off the back of a Wheaties box than you would from Mr. Greenspan.

As for me, I'm wondering what to do with all these potatoes.

All the best,

Chris

Trivia question: Who was in attendance at that 2002 meeting with Greenspan?

Answer: Ben Bernanke.

By Dr. Chris Martenson

http://theendofmoney.com

Dr Martenson is the creator of The End of Money economic seminar series, has extensive experience analyzing and communicating financial information. Dr. Martenson combines a scientist's attention to fact and analysis (PhD, Duke University, Pathology and Toxicology) with a solid understanding of finance and economics (MBA, Cornell, Finance) with strategic thinking (4 years as a management consultant) to produce an insightful and powerful lecture. He is currently devoted to researching, writing and presenting economic and financial analyses delivering his message via his website, lecture series and is currently working on a related book & movie.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.